From a recent article in the Guardian:

A new website is digitising millions of watercolours – to make instantly available a wealth of vital historic imagery that could assist everything from climate research to school teachers.

Hot in the footsteps of Art UK’s ambitious attempt to document every publicly owned artwork in Britain on a single website, a new online project has launched to repeat the project for the world’s watercolours – in particular those that, accidentally or on purpose, documented that world.

Watercolour World is the brainchild of former diplomat Fred Hohler, whose first large-scale digitisation endeavour, the Public Catalogue Foundation, laid the groundwork for Art UK. The idea came to Hohler when he embarked on a tour of Britain’s public collections and realised quite how much there was to do on watercolour alone: Norwich Castle Museum held about 4,500 paintings by a single artist; the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, meanwhile, had somewhere between 200,000-300,000 watercolours in its drawers.

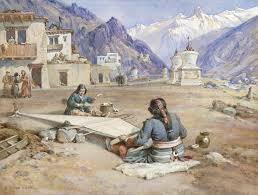

The value – and excitement – of the Watercolour World project, is that it views these historic paintings as documents, not aesthetic objects: visual records of the world at large, in colour, spanning a full 150 years before photography took over as our primary documentary medium. Between the invention of the spool camera around 1900 (which instantly superseded the pocket watercolour box as documentary tool of choice) and the advent of mass commercial colour photography in the 1950s, we lost, in a sense, half a century of colour.

The website, which has launched with about 80,000 works, focuses on pre-1900 documentary paintings: archival information gathering often duly kept in binders and boxes ever since. Some of the artists on the site were professional painters. Others were military draughtsmen, official expedition watercolourists, botanists, surveyors, as well as the untold numbers of amateurs – which Hohler suspects will turn out to have mostly been women, unpaid for their time and skill – who picked up a paintbrush to record the world around them.

The website has started with already digitised pieces from public collections: the Rijksmuseum, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, to name some. Hohler is most excited, though, about what’s hiding in private archives, if only because most owners don’t even realise what they’ve got. “They all say the same thing,” he says: “‘Oh, we don’t have much.’” But often they do – hidden away in an attic or empty trunks in the living room.

This unintentional neglect is why many of the works are in sterling condition: light and handling threaten both pigment and paper; forgetting about artworks doesn’t. While official draughtsmen used the best archival paper, amateurs worked on whatever they could find. Which lends an added incentive to the digitisation Hohler’s team is undertaking: many of these paintings have a shelf life, yet what they depict is potentially of vital importance.

Hohler goes so far as to say that once the collection reaches the critical mass of 1m images, it will be an “absolutely indispensable tool to help us understand today”. From coastal erosion and ice-cap melt to loss of fauna and flora, not to mention direct human destruction (of Palmyra in Syria, say, by Islamic State, or the Seti tomb in Luxor, by tourists) these watercolours serve as an invaluable reference.

Hohler cites the recently reported projected loss of a third of the Himalayan ice-fields. Most of the visual records we have of what those glaciers looked like 150 years ago is in watercolours. Among the images on the website is the first known, yet accidental, picture of Mount Everest, from the 1840s: it’s not even labelled Everest. A lot of the value in these images is similarly accidental. Often it’s the context – replete with treelines, snowlines or waterlines – the artist painted around, for example, the flower they’d set out to record.

Anyone with a phone can send in picture of a historical watercolour they might have lying about, to see if it’s worth cataloguing

As Hohler puts it: “We have in this country all these images about, not this country, but the rest of the world – and they’re stuffed in drawers.” Beyond the UK, he has no idea quite how many images there are, worldwide, to be catalogued, but estimates it to be in the millions. The task is clearly not something his team will ever accomplish alone: the project is as much a call to arms as a public service. Anyone with a phone can send in a picture of a historical watercolour they might have lying about, to see if it’s worth cataloguing. And the more people do so, the more complete a picture of the bygone world this collection will provide.

These watercolours, for the most part, even come with built-in metadata. The website retains the original caption information (even when it’s mistaken) as supplied by the collections the images come from. The team then tags them with appropriate search terms to help people find interesting stuff.

And interesting stuff there is: from the French revolutionary knife grinder with his two canine assistants (search for “dogs”) to the students and their camel at a Marylebone boarding school (there are 366 images tagged with “camel”; search instead for “boarding school”). Teachers will have a field day. And, Hohler’s team suspects, so will any punter as curious about their own neck of the woods as they are about far-flung lands.

Image: A Tibetan Weaver, 1895, by William Simpson from Watercolour World. Photograph: Private collection